Carl O. Schuster,

Captain, USN (Ret)

Adjunct Professor, Hawaii Pacific University

Diplomacy and Military Science Program

Although not unexpected, China’s neighbors should take warning from China’s rejection of the International Court of Arbitration ruling on its South China Sea claims. Beijing has used the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea as the basis for its actions and claims in both the South China Sea and elsewhere. Now it says the court has no jurisdiction over waters Beijing claims as its own; claims it has argued were based on the convention. Perhaps without realizing it, China’s rhetoric constitutes an admission it will behave like a traditional great power, bullying weaker nations when it can and adhering to agreements it has signed only when it suits Beijing. It is also clear China will ignore any G-7 or other international statements urging it to comply. Its veto on the UN Security Council ensures there will be no UN action. The question for the Philippines and China’s neighbors is; given China’s recent behavior and growing assertiveness, is it seeking negotiations to achieve an agreement that balances the interests of both parties involved or merely to buy time for and justify aggressive actions its leaders have already decided to take. More importantly, can China be trusted to adhere to any agreement it signs? Whatever the answers, it is clear Beijing does not see the Sino-Philippines territorial dispute in the South China Sea to be resolved. The Philippines and other regional countries must now determine what is China’s ultimate goal or end game in the South China Sea. .

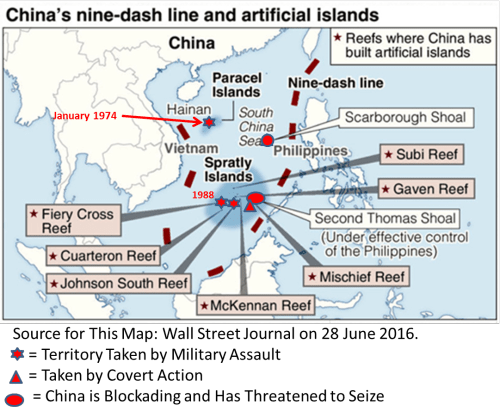

One key element in making that determination lies in Beijing’s actions and words of the last 42 years (Map 1). The campaign to control the South China Sea began in January 1974, when China seized the Paracel Islands from the then-collapsing South Vietnamese regime. Since then China, has been slowly and incrementally seizing territory in the nearby Spratly Islands by a combination of military assault (Johnson South Reef in 1988) , covert military occupation (Mischief Reef in 1996) or blockade (Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal since 2012) These are but the physical indicators of China’s end game not just in the South China Sea but throughout what its National Defense White paper defined as the “First Island Chain,” (Map 2) which encompasses the territory within the so-called 9-dashed line and all the territories Beijing claims were once part of Dynastic China (including Taiwan, and the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands).

Since 2012, armed Chinese fishing craft organized as part of its “People’s Maritime Militia” have been boarding and intimidating Vietnam’s fishermen. In fact, Chinese coast guard vessels ram and sink Vietnamese fishing boats in the South China Sea on almost a weekly basis, often making no effort to rescue the crewmen of the sunken craft. Vietnam has begun to arm its fishermen in response. However, neither Vietnam nor any other claimant to the Spratly Islands chain was prepared to stop the massive land reclamation project China initiated in those waters in the summer of 2014. More recently, China closed the waters and air space where it conducted its pre-arbitration ruling military exercises to all traffic. Traditionally, countries issue Notices to Airmen and Mariners warning them to beware of the exercises and avoid exercise participants, a far cry from closing the air space and waters to civilian usage. China did this despite assuring the international community in 2013 that its territorial claims would not lead to it denying the use of those waters. A promise broken once has no credibility, whatever the justification. It can and will be broken again.

China’s military actions simply reflected the incremental physical component of China’s effort. If that wasn’t warning enough, China’s 2009 and subsequent Defense White paper directed the military to defend the nation’s territorial integrity and sovereignty over its national and maritime territories. It also stated the goal of controlling the waters and air space within the First Island Chain, which encompasses all of China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea and the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. In the latter instance, Beijing declared an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the islands in an effort to gain control over the air space above. Beijing has learned from that mistake. It will not declare a South China Sea ADIZ until it has emplaced the capability to enforce it.

China has also been conducting a global propaganda effort to gain international support for its territorial claims in the South China. The government-owned news outlet, CCTV, has been broadcasting “documentaries” about the South China Sea for at least three years. In addition to speaking how its territorial claims are in accordance with the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the CCTV reports highlight the nearly thousand years of Chinese fishing activities there and extolled China’s efforts to protect the delicate marine environment and resources. None of those reports mentioned the Philippines or Vietnamese fishing activities of similar duration in those waters. CCTV is silent about the Chinese People’s Maritime Militia bullying of those countries’ fisherman and the Chinese Coast Guard’s ramming and sinking of Vietnamese fishing boats. Nor did CCTV include any mention of China’s military assaults to seize South China Sea territories, or the fortified “fisherman’s shelters constructed on some of the islands. Finally, neither the CCTV reports nor those of international conservation groups discuss the destruction of thousands of acres of fragile coral and other sensitive marine habitats and life that China’s artificial island construction program has wrought on the region’s ecosystems.

China’s propaganda on these issues has changed over the last year in response to the Philippines taking its case to the UNCLOS Court of Arbitration. After years of justifying its claims in accordance with UNCLOS, Beijing now asserts that the treaty and its court has no authority over the issue because the South China Sea is Chinese territorial waters. China’s media outlets have become increasingly strident as the Court’s 12 July announcement of its decision approaches, saying it will reject any decision that does not validate its territorial claims. China has also applied economic leverage, delaying the unloading and transshipment of perishable Philippine goods at Chinese ports. Beijing has also issued veiled threats about losing patience with Manila and removing the Philippine Tank Landing Ship BRP Sierre Madre (LT-57) and embarked garrison from Second Thomas Shoal. Chinese authorities also offered to negotiate their conflicting claims if Manila also rejects the court’s decision. Meanwhile, China’s artificial island construction program and South China Sea military buildup continues. The challenge, for both the United States and other regional players, is how to prevent China gaining control over those critical waters without creating a situation no one wants or can afford.

Achieving that requires a multi-lateral approach akin to China/s. In addition to continuing military exercises with and assistance to regional countries, American and other countries’ Freedom of Navigation (FON) operations should adhere to traditional challenge responses, (e.g. we are transiting international waters as allowed under international law) , avoiding the mixed message that accompanies a declaration of “innocent passage” that justifies transiting territorial waters. Additionally, American leaders should publicly discuss if not apply the leverage that comes with being China’s largest export market. As an exporting nation, China is sensitive to market constraints and competition. Several of the victims of its South China Sea actions are also its competitors on the global scene. The Peoples Republic of China’s (PRC’s) cyber-actions, industrial piracy and inconsistent legal culture have raised the costs and risks for foreign companies investing and operating in that country. Shifting their investment to friendlier climes makes fiscal sense and would get Beijing’s attention. So would any additional screening and inspection of Chinese cargoes entering the United States. The Philippines and Vietnam are more “investor friendly” than China and will welcome Western investment. It is not an immediate solution but China is playing the “long game” and so should the other countries affected by China’s actions, especially the U.S.

The West also needs to counter China’s propaganda. First, regional officials and hopefully environmental groups should point out the discrepancies between Beijing’s claims of protecting the South China Sea’s maritime environment and the reality of its actions. Second, Washington should work with Hanoi in condemning China’s sinking of Vietnamese fishing boats, particularly the cases where the crews are left to their own devices. The Chinese blockade of Scarborough Shoal should also be exposed. Then there is the issue of China’s statements that its claims are based on “historical precedence,” stating that its fishermen and commercial trading ships have plied those waters for centuries. The same can be said for Vietnamese, Malaysian and Philippine fishermen and mercantile shipping. In fact, prior to the Nationalist Chinese government laying claim to the waters in 1947, the Ming Dynasty was the last Chinese government to claim and garrison those waters. At present, five other governments claim contending parts of the South China Sea as Economic Exclusion Zones or Territorial Waters. Those governments include Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam and Taiwan. The last three of these share China’s territorial claims and basis for them.

China’s construction and garrisoning activities indicate Beijing’s intent to both claim the South China Sea as its own and ultimately control the sea lanes that pass through and the air space that lies over it (see Map 3). If China is allowed to achieve that goal, it will enjoy a stranglehold on the 30% of the world trade that passes through those waters and more importantly, be in a position to block Japan’s access to the trade routes through the Malacca Straits, preventing its exports from reaching South Asian and European markets and denying Japan the energy and material imports so vital to its national economy and survival (see Map 3). . The Chinese people’s desire to redress their “Century of Humiliation” is understandable but their neighbors were also dominated by foreign powers during that same century. A wise man once said people and nations are prisoners of their past experiences. The best people realize they are not the only ones in the room with a painful history and join with the others in applying their shared lessons to make a better future. Behaving like the imperialist powers of the past reduces China to just another bully on the regional scene. Looking beyond the South China Sea issue, China must be made aware of the costs of ignoring international law, especially when they reject components of the treaties they have signed. Doing so diminishes the credibility of every agreement they have entered

Peacefully deterring further Chinese aggression will require a mixture of diplomatic and economic pressure; and moderate, rational military activities conducted within the auspices of international law such as joint naval patrols, small scale military exercises and assistance to Southeast Asian nations. Most of all, all the countries with an interest in maintaining freedom of navigation through and over the South China Sea must educate their citizens and the global community on the common interest in and need to sustain that freedom. China must understand its territorial grab has no basis in international law and that aggressive military actions are unacceptable and will carry an unacceptable cost in political goodwill. That is why the United States is conducting freedom of navigation operations in the South China and other countries with an interest in maintaining the freedom to navigate those waters, such as Australia, India and Japan, are considering similar operations in the South China Sea. Also, like the United States, those countries are seeking ways to assist the Southeast Asian countries bordering the South China in improving their security capabilities.

Map 1

Map 2

Map 3

Captain Carl O. Schuster, USN (Ret). A 1974 Graduate of the University of South Carolina NROTC battalion, Captain Schuster earned an MA in International Relations from the University of Southern California in 1989. Initially commissioned as a surface line officer, Captain Schuster served on a variety of U.S. and foreign ships and submarines as well in several field and staff assignments before finishing his career as Director of Operations at the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific. He retired from the naval service in June 1999..

He is a visiting Assistant Professor and Instructor at Hawaii Pacific University and the Naval War College, respectively. Among his classes are Strategy and War; Chinese Military Doctrine and Strategy, Present and Future Conflicts of the 21st Century, 20th Century Unconventional Warfare and Special Forces’ Operations; and 20th Century Deception Operations. Captain Schuster is also a member of the Oxford University Roundtable and a published author with over 614 articles in print. He wrote the “Chinese Maritime Traditions” Chapter for the King’s College study, Sea Power and the Asia-Pacific and has been the assistant editor for three books; World War II in Europe, Chiefs of Staff and German Military History. He is also the Weapons Technology and Asia-Pacific issues editor for ABC-CLIO publishing and weapons editor for Vietnam Magazine.